Mammals will most likely be wiped from the face of the Earth by our planet's next supercontinent, a new study has revealed, according to Live Science.

By modeling the heat tolerance of mammals alongside Earth's climatic conditions 250 million years into the future, scientists have discovered that the formation of the most probable next supercontinent — called Pangaea Ultima — will bring about the likely extinction of our animal order.

The researchers made the prediction using a climate model that factored in the changes to land surface temperature of a new supercontinent; alongside increases to the intensity of the sun's radiation and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The study was published Sept. 25 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

"A supercontinent seemingly creates conditions that more easily lead to mass extinction," first-author Alexander Farnsworth, a climatologist at the University of Bristol in the U.K. told Live Science. "[Supercontinent formation] has coincided with four of the last five mass extinctions in the geologic past."

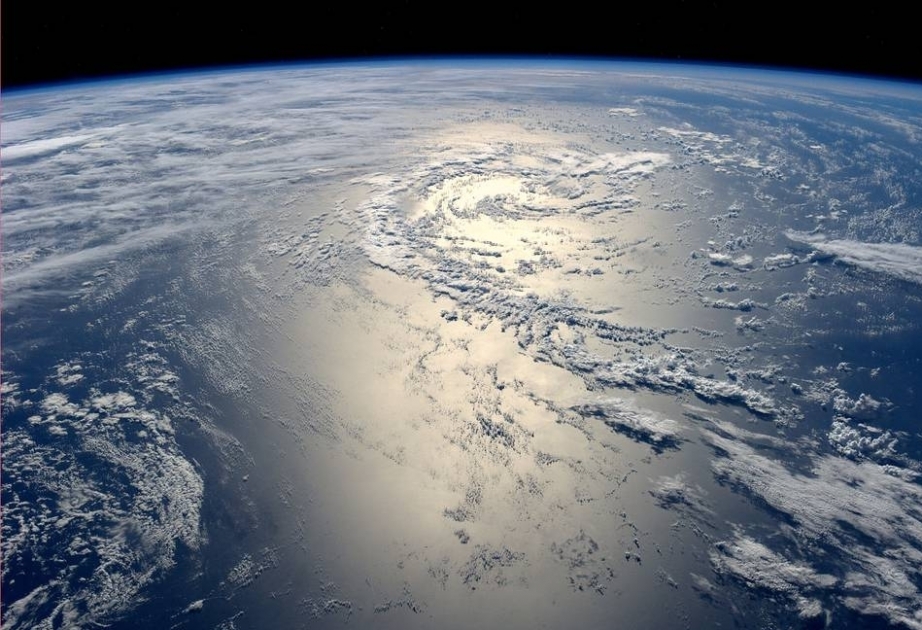

Earth's foundations are far from static, and consist of plates of solid rock floating on a churning ocean of magma. Over the past 2 billion years, magmatic convection currents have repeatedly pulled these plates apart to form oceans and continents before smashing them together again into a supercontinent. This occurs in cycles of roughly once every 600 million years.

Scientists expect the next supercontinent to form in 250 million years time, when Earth's landmasses crash together (most probably at the equator) to form Pangaea Ultima.

This new continent will be hot: not only will much of its equatorial landmass lack the cooling effect brought about by oceans; but it will absorb more radiation from an older, more active sun and be swamped in significantly more carbon dioxide due to volcanic activity.

This likely spells doom for mammals. The animal order — sporting adaptations such as sweat glands and a circulatory system that removes warmth — is fairly good at coping with high temperatures. Yet crank the heat up past 104 degrees Fahrenheit (40 degrees Celsius) in dry heat, or 95 F (35 C) when it is humid, and these temperature regulators start to break down; preventing the removal of dangerous excess heat from bodies.

To figure out just how inhabitable the future Earth will be, the scientists turned to a supercomputer-run climate model that forecast temperatures and humidities across Pangaea Ultima.

With most of Earth's landmass locked-in; the aging sun emitting 2.5% more radiation; and atmospheric carbon dioxide levels increasing to 1.5 times today's levels — the simulation found that only 8% of the supercontinent's land would be habitable for mammals.

The scientists expect that much of this temperature increase may come in the wake of massive eruptions forming carbon-belching, lava-piled regions known as large igneous provinces. Driven by the powerful, crunching tectonics of the colliding plates, the growth of these hellish provinces will leave mammals with little time to adapt to soaring temperatures.

"While there are some very specialist mammals today that can inhabit regions such as the Sahara, it remains to be seen whether these mammals would become preferentially selected and descendants would reradiate into Pangaea Ultima and dominate," Farnsworth said. "Perhaps reptiles are better adapted? Or something completely different?"

The researchers say that it also remains a possibility that Pangaea Ultima threatens the end of all life, especially if temperatures get so hot that plants can no longer perform photosynthesis. But plants' adaptability to temperature, as well as the hardiness of future marine ecosystems, will take more research to understand, they said.

Pangaea Ultima is also not the only supercontinent that may form, however: cooler ones, such as the polar-centered 'Amasia' have also been predicted by scientists. By a hair's breadth, mammals may survive after all.