By JERUSALEM POST STAFF

The irrigation network consists of over 200 primary canals, some of which stretch up to nine kilometers in length and are between two and five meters wide.

A team of researchers identified and mapped a vast network of irrigation canals near Eridu, considered the oldest city in history. The discovery reveals one of the region's most well-preserved networks of canals, demonstrating the knowledge of hydraulic engineering required for their construction and maintenance.

Eridu, located in southern Iraq in the heart of ancient Mesopotamia, is the southernmost of all the great Mesopotamian cities, as noted in the Sumerian King List. Inhabited from the sixth to the first millennium BCE, the city preserves one of the oldest and best-preserved irrigation networks in Mesopotamia.

The irrigation network consists of over 200 primary canals, some of which stretch up to nine kilometers in length and are between two and five meters wide. Additionally, more than 4,000 smaller canals were identified, ranging from ten to 200 meters in length, directing water to farmland. Around 700 farms were organized along these secondary canals, reflecting an intensive and well-structured agricultural system based on equitable water distribution.

The ability to divert water from rivers through canals was crucial for the sustainability of urban settlements in Mesopotamia. Eridu had a highly organized water distribution system that supported early urban settlements. The discovery near Eridu sheds new light on early water management techniques, confirming that agriculture in Mesopotamia was not only dependent on the natural fertility of the soil but also on sophisticated hydraulic planning.

Archaeologists used an interdisciplinary approach that included geomorphological analysis, historical map reviews, and remote sensing technology. High-resolution satellite imagery, including images from the 1960s CORONA program, drone footage, and ground photography were used to validate the canal mapping findings.

One of the key methods for distinguishing natural canals from artificial ones was the analysis of water flow patterns, topography, current directions, and the presence of hydraulic control structures. Hydraulic control structures, including dikes and natural or artificial breaches in river dikes, allowed the controlled distribution of water in the floodplain.

Long ago, the Euphrates River shifted course, forcing people to abandon the area around Eridu. This abandonment allowed the archaeological landscape of the Eridu region to remain relatively intact, making it a rare exception to the pattern of alteration seen in other areas. Most ancient irrigation structures in Mesopotamia have been buried under river sedimentation or replaced by later networks, making it difficult to study the earliest agricultural systems in detail.

The stability of the Euphrates River allowed the main canals in the Eridu region to retain their functionality for centuries. Many of the canals identified near Eridu remain intact, and the ability to trace such a detailed irrigation system shows how early civilizations adapted to their environment.

The findings confirm that Eridu was once a center of sophisticated agricultural planning, necessitating a high level of social organization to ensure the operation of the irrigation canals. The irrigation network indicates engineering expertise among the people of Eridu, which researchers hope to correlate with written records from the time.

While the discovery confirms the irrigation network's importance, researchers now face the challenge of establishing a precise timeline for its construction and use. They plan to excavate key sites and conduct stratigraphic excavations to analyze soil layers and sediment remains for sediment dating, aiming to date the use of canals more accurately.

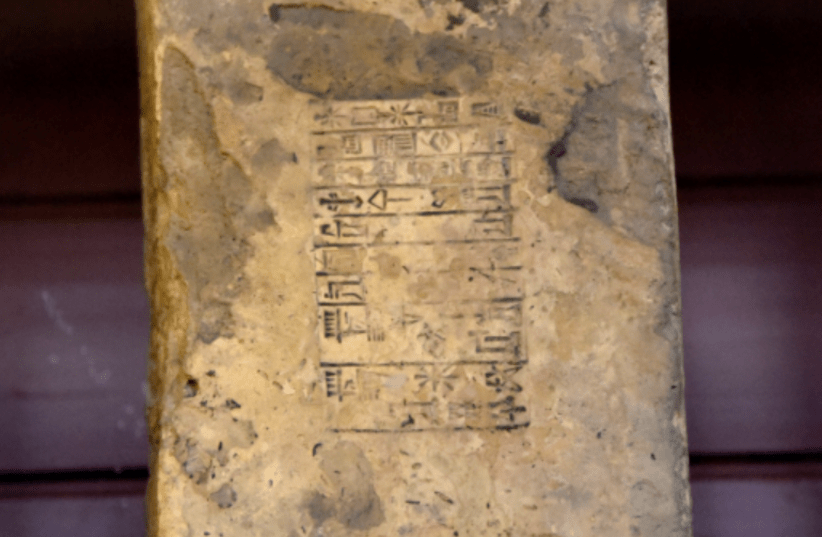

Researchers also aim to compare their findings with cuneiform inscriptions to gain further insights into the irrigation practices of ancient civilizations and to correlate written records with tangible data. This comparison could provide new insights into water management in ancient Mesopotamian states.