University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and UPMC Hillman Cancer Center scientists have discovered a novel subset of cancer-fighting immune cells that reside outside of their normal neighborhood—known as the tertiary lymphoid structure—where they become frustratingly dysfunctional when in close contact with tumors, MedicalXpress reported.

Described in the journal Science Translational Medicine, the finding gives oncologists a new target for developing immunotherapies: double negative memory B cells, so-called because they are negative for two markers found on the surface of their more common brethren. They may also be a useful diagnostic marker when creating treatment plans.

"The responsiveness of B cells is an important part of whether a patient with cancer does well or not," said senior author Tullia Bruno, Ph.D., assistant professor of immunology at Pitt and a member of the Cancer Immunology and Immunotherapy Program and Tumor Microenvironment Center at UPMC Hillman.

"By better understanding different types of B cells and their location, we can aim to reinvigorate them and unleash their anti-tumor potential."

B cells are white blood cells, produced in the bone marrow, that neutralize pathogens—such as bacteria, viruses and cancer cells—and tag them for removal from the body. Memory B cells are particularly long-lived and "remember" pathogens, priming the immune system to respond quickly if it encounters the pathogen again.

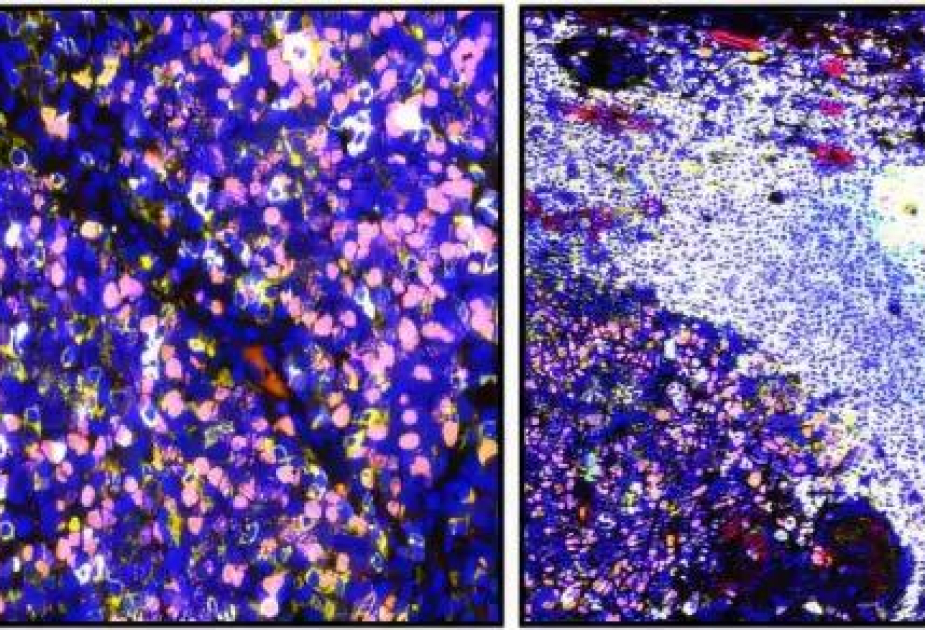

When someone has cancer or a chronic infection, their body may form tertiary lymphoid structures near or within the cancer. The structures contain immune cells—predominantly B cells—and patients with the structures tend to have better outcomes.

While doing her graduate work in Pitt's Program in Microbiology and Immunology, co-lead author Ayana Ruffin, Ph.D., now a postdoctoral research fellow at Emory University, observed that memory B cells were abundant in the blood of head and neck cancer patients—particularly those doing well.

Curious, she pored over existing research and found that, while double negative memory B cells were well-characterized in chronic infection and autoimmune studies, little was known about their role in cancer.

She turned from blood to tumor samples and found double negative memory B cells there as well—but they were more dysfunctional, displaying features of exhaustion.

Exhaustion is something cancer immunologists have been focused on with T cells—immune cells that destroy pathogens, such as cancer. But Ruffin was one of the first to observe this exhaustion in memory B cells in and near tumors, outside of the tertiary lymphoid structure.

"Historically, B cells have largely been ignored in the cancer research field, with scientists instead favoring research on 'killer' T cells," said co-lead author Allison Casey, Ph.D. candidate in Pitt's Molecular Genetics and Developmental Biology graduate program who took over the research when Ruffin graduated.

"But B cells are really unique—they're like the cool person at school who talks to everyone. They can use antibodies to neutralize pathogens and engage other immune cells. They educate T cells so they know to destroy cancer or infections."

Casey and the research team are now exploring existing cancer immunotherapies—which are mostly aimed at helping T cells fight cancer—to see if there are ways to modify them to also boost memory B cells. They're also investigating B cell therapies used in autoimmune diseases to see if they can be leveraged to fight cancer.

"This is a really good example of when a graduate student comes to you with an awesome idea and runs with it—she breaks new ground in the field," Bruno said. "This research is a testament to what happens when students are encouraged to think creatively."