Jerusalem Post

ByZALMAN EISENSTOCK

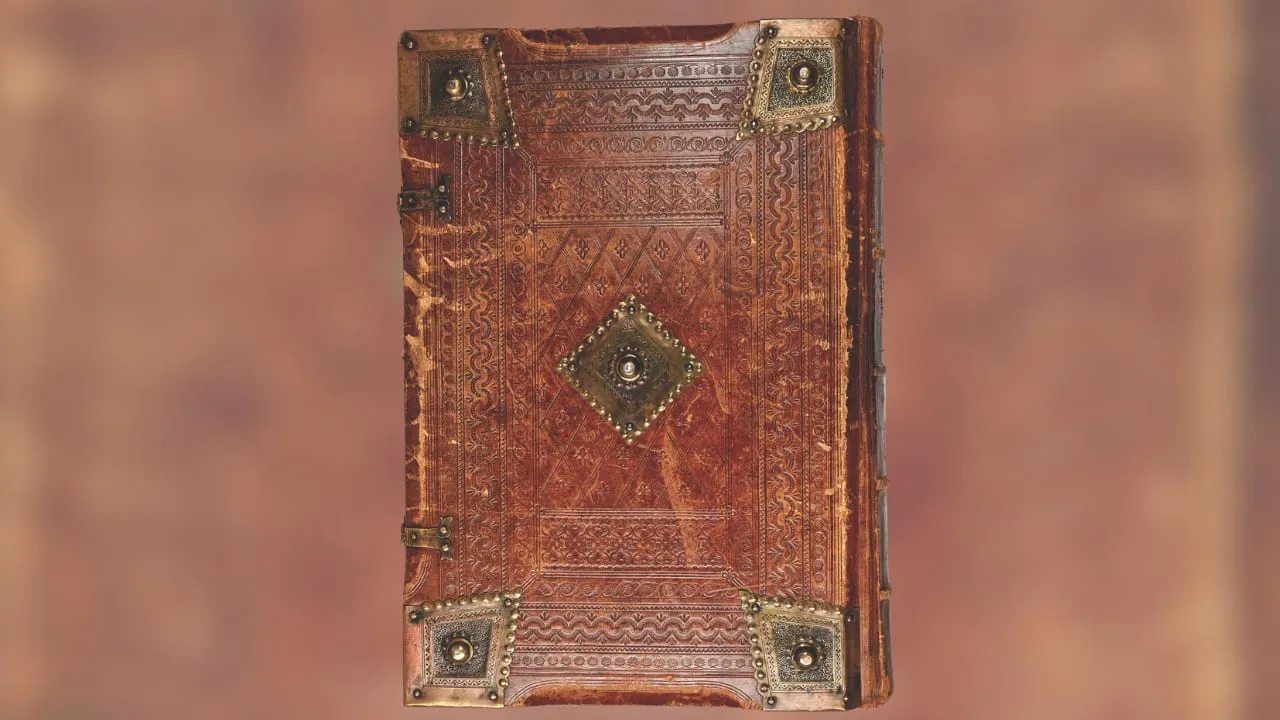

The first volume of the machzor was completed in1272 in Wurzburg, Germany. Today, it is displayed in the National Library in Jerusalem.

Throughout the Holocaust that devastated European Jewry, there were innumerable stories of the survival of men, women, and children. There were also many accounts of survival not of people but of religious objects: Torah scrolls, siddurim, and machzorim.

These accounts reveal a great deal about how precious and significant these objects were to many different communities. The following is the story of a machzor that was handwritten in 1272 in Wurzburg, Germany, and eventually made its way to Israel.

The first Jews arrived in Wurzburg at the end of the 11th century, having escaped the Rhine communities that had been ravaged by massacres perpetrated by Crusaders in 1096. Among them were rabbis, scribes, artisans, and moneylenders. For two centuries, the Jewish community grew and established synagogues, schools, and mikvehs (ritual baths).

Every text that was produced during that period was handwritten on parchment. One of those items was a machzor written by the scribe Simhah ben Yehuda and beautifully illuminated by Shemiah Hazorfati. One source states that it took Ben Yehuda almost an entire year to carefully copy all of the tefillot (prayers) contained within it. While today we associate a machzor primarily with the High Holy Days, this particular machzor also contained prayers for Shabbat and the three pilgrimage festivals of Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot.

A special prayer added on the seventh day of Passover is one for dew, and there is a note written in Yiddish in the margin that states: “Let a good day shine for him who will carry this machzor to the synagogue.” Apparently, the precious prayer book was not kept in the synagogue itself but in someone’s home. Unlike today’s siddurim and machzorim, which are easily carried, this one was extremely heavy. In addition, it includes many famous piyutim (Jewish liturgical poetry), among them “U’nataneh Tokef” and “Kol Nidrei” recited on Yom Kippur night.

Famous Torah scholars of Worms

The first volume of the machzor was completed on January 2, 1272, and was used by cantors in the local synagogue for eight years. In 1280, it was moved to Worms, Germany, where a second volume was added. It remained there for more than 650 years.

Worms was renowned for its Torah scholars. Rashi studied there briefly with Rabbi Yaakov ben Yakar, a student of Rabbenu Gershom. Rabbi Meir of Rothenburg served as the city’s chief rabbi toward the end of his life. Known as the Maharam, he was imprisoned in Worms and famously forbade the Jewish community from raising funds to ransom him.

The Worms Machzor remained in use for more than six centuries, until 1938.

Historical manuscripts survive Nazi attack

This is when the story of the Worms Machzor enters a remarkable chapter of survival and rescue. On the night of November 9, 1938, Nazi troops and Gestapo soldiers set fire to more than 90 synagogues across Germany. The main synagogue in Worms was burned to the ground. However, the archives containing historical manuscripts, including the machzor, were stored in a different building and remained intact.

The head archivist in Worms at the time was Dr. Friedrich Maria Illert, who searched desperately for the missing archives but was unable to locate them. It was not until 1943 that the collection was rediscovered, fully intact.

That summer, Illert was summoned to a Gestapo office and asked to accompany a high-ranking officer to the basement of a building to help decipher the language of books stored there. Upon examining the texts, Illert realized he was standing among the Worms archives, which included the massive machzor.

Days after making this discovery, he made a courageous decision and slowly transferred the entire collection to the tower of a local cathedral. There, the precious archives miraculously survived Allied bombing until the end of the war.

From 1943 until 1957, the machzor remained in the cathedral. After obtaining the necessary permits, Illert arranged for its transfer to the National Library in Jerusalem. Several years ago, a new building was completed to house the library’s documents and manuscripts, located across the road from the Israel Museum.

A personal connection

A few weeks ago, I made my first visit to the National Library to explore its collections. While walking among the display cases, I stopped abruptly at a sign identifying the Worms Machzor, whose existence I had not previously known about. It immediately piqued my interest because my father-in-law, Rabbi Norbert Weinberg, is a descendant of the Wurzburger Rav, Rabbi Seligman Bamberger.

Bamberger served as chief rabbi of Wurzburg from 1840 until his death in 1878 and, together with Rabbi Shimshon Rafael Hirsch, was among the leading Orthodox rabbis in Germany. In addition to his rabbinical responsibilities, he authored several important works in the realms of Jewish law and prayer.

The last rabbi of Wurzburg was my father-in-law’s grandfather, Rabbi Menachem Weinberg. Efforts were made to obtain visas for him and his wife, but they were unsuccessful. Tragically, both were deported to the Terezin transit camp near Prague, where they perished in 1943. Thousands of other Jews were also sent to Terezin, many of whom were later transported to and met their demise at Auschwitz.

Fortunately, my father-in-law’s family escaped Germany in 1938. After spending the war years in England, they moved to Yonkers, New York. Like the beautiful Worms Machzor that survived the Holocaust and ultimately reached Israel, my father-in-law also made aliyah about 10 years ago and now lives in Efrat with his wife, surrounded by children, numerous grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.■

The writer is an educator, freelance writer, and author of Psalms: An Eternal Treasure.