For thousands of years, humans have gazed up at the moon, wondering what secrets it holds. Now, new research suggests that water on the moon’s surface is more widespread than we thought — even in places bathed in sunlight.

Roger Clark, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute, and his team have uncovered evidence that could change our understanding of the moon’s resources, according to Space.com.

“Future astronauts may be able to find water even near the equator by exploiting these water-rich areas,” Clark said. “Previously, it was thought that only the polar region, and in particular, the deeply shadowed craters at the poles were where water could be found in abundance.”

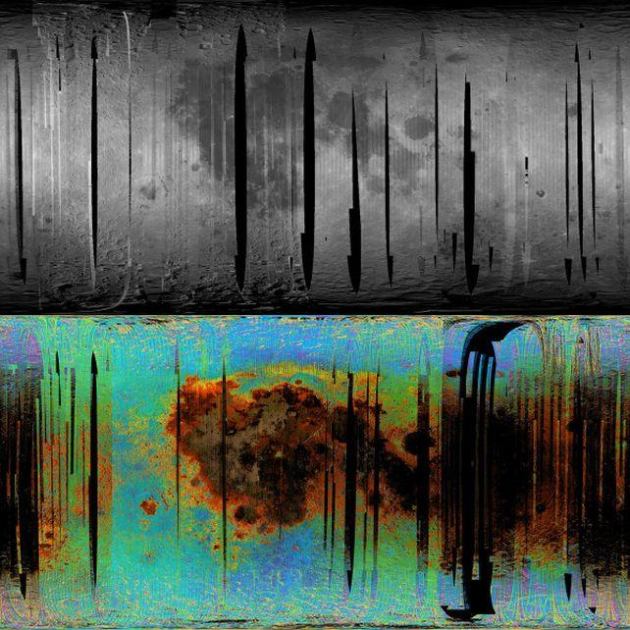

Back in 2008 and 2009, the Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft orbited the moon, collecting detailed maps of its surface using the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3) imaging spectrometer.

The M3 instrument wasn’t your average camera — it captured 85 different colors from the visible spectrum into the infrared range.

This allowed the team to search for the unique fingerprints of water and hydroxyl in the sunlight reflected off the lunar surface.

Imagine trying to spot a drop of water on a vast desert. Sounds tricky, right?

But by using infrared spectroscopy, scientists can detect tiny amounts of water and hydroxyl (a molecule made of one hydrogen and one oxygen atom) by the way they absorb light.

Different materials absorb and reflect light differently, giving each a unique spectral signature.

“Just like we see different colors from different materials, the infrared spectrometer can see many (infrared) colors to better determine the composition, including the water (H2O) and hydroxyl (OH),” Clark explained.

This means that even in sunlit areas, where water was thought to be scarce, we can now detect these vital molecules.

One of the key findings is that meteor impacts play a significant role in distributing water across the moon.

When meteors crash into the surface, they excavate water-rich rocks from beneath, scattering them across all latitudes.

This challenges the long-held belief that useful amounts of water are only found in the dark, frigid craters near the poles.

By studying where this water is located, scientists can learn more about the moon’s geological history. Plus, it opens up new possibilities for future lunar missions.

If astronauts can find water closer to the equator, it could make long-term habitation more feasible.

But there’s a catch. Water on the moon doesn’t behave quite like it does on Earth. It’s what’s known as “metastable,” meaning it’s slowly broken down over millions of years.

“By studying the location and geologic context, we were able to show that water in the lunar surface is metastable,” Clark noted. “H2O is slowly destroyed over millions of years, but with hydroxyl, OH, remaining.”

So, while water molecules may degrade over time, hydroxyl sticks around. This hydroxyl can potentially be combined to create water and even oxygen — a valuable resource for astronauts.

The moon’s surface is also coated with a thin layer of hydroxyl, thanks to the solar wind. Protons from the sun slam into the lunar soil, interacting with oxygen in minerals to form hydroxyl in a process called space weathering. It’s like a constant drizzle of particles reshaping the very surface of the moon.

“Elsewhere on the lunar surface, there appears a patina of hydroxyl, probably created from solar wind protons impacting the lunar surface,” Clark said. This means that the moon is continually evolving, even without an atmosphere or weather as we know it.

Putting all these pieces together reveals a moon that’s more geologically complex than we imagined. “Both cratering and volcanic activity can bring water-rich materials to the surface, and both are observed in the lunar data,” Clark pointed out.

The moon primarily consists of two types of rocks: dark basaltic mare, similar to lava flows in Hawaii, and lighter anorthosite rocks that make up the highlands.

Interestingly, the anorthosites contain a lot of water, while the basalts have very little. This difference affects where water and hydroxyl are found and how they’re bonded within the minerals.

Another intriguing aspect is how the strength of water and hydroxyl signals changes with the lunar day. When the sun is low on the horizon, the infrared absorptions become stronger.

This led scientists to think that water might be moving around the moon daily. However, Clark’s team found a different explanation.

The effect is due to a thin surface layer that’s different from the deeper soil. When the sun is low, light passes through more of this top layer, enhancing the absorption signals.

So, while there might still be some movement of water, the layering of the soil plays a significant role.