By Zack Rothbart

In his new book ‘The Islamic Moses,’ US-based author Mustafa Akyol turns to the Quran’s focus on a shared prophet to highlight a historic closeness and foster interfaith relations

Wishing to better understand Islam, a Christian friend once asked US-based Turkish writer, intellectual and journalist Mustafa Akyol to recommend an English translation of the Quran for him to read. A few weeks later, after completing Muhammad Abdel-Haleem’s “The Qur’an: A New Translation,” the friend continued his conversation with Akyol. He had some thoughts and had been grappling with some passages that he found notably opaque or troublesome — yet one thing struck him as the biggest surprise of all.

“I was expecting to read about the life of Muhammad, but instead I read about the life of Moses more than anything else,” the friend wrote.

Moses is mentioned 137 times in the Quran, while Muhammad is mentioned just four times. And who is the second most common character in Islam’s holiest text? Another figure from the Jewish Bible — Moses’s nemesis, Pharaoh.

That certainly is not by chance, as Akyol points out in his new book, “The Islamic Moses: How the Prophet Inspired Jews and Muslims to Flourish Together and Change the World.”

The biblical characters and narrative were, in fact, intentionally central to the new faith Muhammad was cultivating and promoting across Arabia and beyond some 14 centuries ago.

Moses and his story were emulated by Muhammad, and the parallels are not hard to spot. Both men started as unlikely leaders — Moses, slow of speech, and Muhammad illiterate — and yet both ultimately led massively successful migratory, nation-building and military efforts alongside the establishment of new religious-legal systems: Jewish halacha and Islamic sharia.

In the book, Akyol examines further theological parallels, yet also explores historical encounters between the Jewish and Islamic worlds. The author finds these interactions especially important in the current geopolitical climate, in which many forget that for much of history, the Judeo-Islamic tradition was much more peaceful, fruitful and coherent than the Judeo-Christian one.

Some of those encounters — such as the mass migration of exiled Iberian Jews into Muslim lands in the 15th and 16th centuries — are well-known. Others — like Jews celebrating the initial Muslim conquest of Jerusalem, which facilitated some 1,400 years of nearly uninterrupted Jewish settlement in the Holy City after Christians had long barred them from residing there — are less well-known.

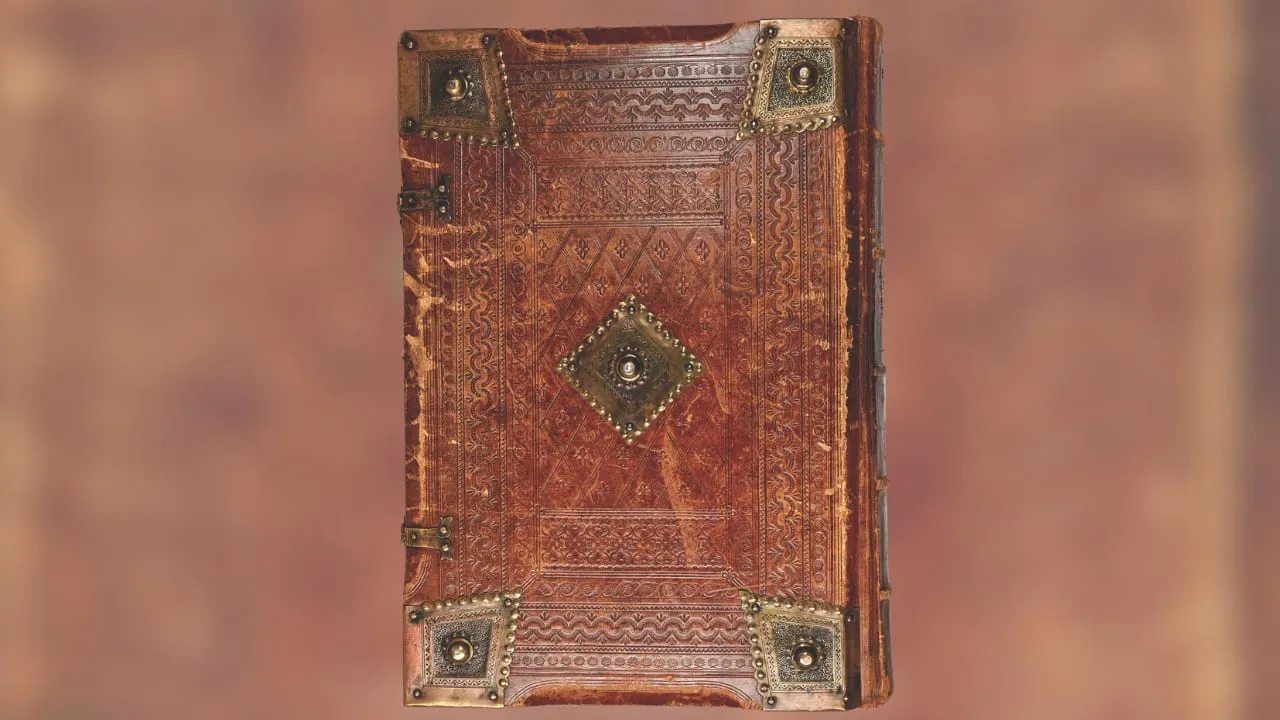

Muhammad leads Abraham, Moses, Jesus and others in prayer. Persian miniature, 15th century. (Public domain)

Wishing to better understand Islam, a Christian friend once asked US-based Turkish writer, intellectual and journalist Mustafa Akyol to recommend an English translation of the Quran for him to read. A few weeks later, after completing Muhammad Abdel-Haleem’s “The Qur’an: A New Translation,” the friend continued his conversation with Akyol. He had some thoughts and had been grappling with some passages that he found notably opaque or troublesome — yet one thing struck him as the biggest surprise of all.

“I was expecting to read about the life of Muhammad, but instead I read about the life of Moses more than anything else,” the friend wrote.

Moses is mentioned 137 times in the Quran, while Muhammad is mentioned just four times. And who is the second most common character in Islam’s holiest text? Another figure from the Jewish Bible — Moses’s nemesis, Pharaoh.

That certainly is not by chance, as Akyol points out in his new book, “The Islamic Moses: How the Prophet Inspired Jews and Muslims to Flourish Together and Change the World.”

The biblical characters and narrative were, in fact, intentionally central to the new faith Muhammad was cultivating and promoting across Arabia and beyond some 14 centuries ago.

Get The Times of Israel's Daily Editionby email and never miss our top stories

Newsletter email address Get it

By signing up, you agree to the terms

Moses and his story were emulated by Muhammad, and the parallels are not hard to spot. Both men started as unlikely leaders — Moses, slow of speech, and Muhammad illiterate — and yet both ultimately led massively successful migratory, nation-building and military efforts alongside the establishment of new religious-legal systems: Jewish halacha and Islamic sharia.

In the book, Akyol examines further theological parallels, yet also explores historical encounters between the Jewish and Islamic worlds. The author finds these interactions especially important in the current geopolitical climate, in which many forget that for much of history, the Judeo-Islamic tradition was much more peaceful, fruitful and coherent than the Judeo-Christian one.

A partial view of the Nabi Musa complex, where the tomb of Prophet Moses is believed to be located, in the Judean Desert near the West Bank town of Jericho, on January 2, 2021. (HAZEM BADER / AFP)

Some of those encounters — such as the mass migration of exiled Iberian Jews into Muslim lands in the 15th and 16th centuries — are well-known. Others — like Jews celebrating the initial Muslim conquest of Jerusalem, which facilitated some 1,400 years of nearly uninterrupted Jewish settlement in the Holy City after Christians had long barred them from residing there — are less well-known.

Advertisement

Akyol doesn’t overlook some of the darker historical periods in Jewish-Muslim relations, such as the persecution and forced conversions under the Almohad Caliphate, though he treats these as largely the exception rather than the rule, and they are certainly not the book’s focus.

Mustafa Akyol. (Richie Downs for Cato Institute)

A senior fellow at the Cato Institute and a prolific author, Akyol often explores the intersection of Islam and modernity, as well as other cultures and faiths. His previous books include “Islam Without Extremes: A Muslim Case for Liberty”; “Reopening Muslim Minds: A Return to Reason, Freedom, and Tolerance”; and, perhaps most similar to his latest work, “The Islamic Jesus: How the King of the Jews Became a Prophet of the Muslims.”

The Times of Israel asked Akyol about the impetus for examining the Islamic Moses, what most surprised him during the course of his research, and what relevance he sees in the Judeo-Islamic tradition in today’s post-October 7 reality.

The Times of Israel: What triggered you to explore this topic?

Mustafa Akyol: For decades, as a believing Muslim, I studied the Quran and the Islamic tradition with a growingly interfaith perspective. One thing that struck me is the similarities between Islam and Judaism, from their staunch monotheism to dietary laws, to the primacy of law, the halacha and the sharia, respectively. The more I read about these similarities, as well as the historical connections between Jews and Muslims, I became aware of a “Judeo-Islamic tradition,” as the late great Bernard Lewis called it, and I wanted to tell this story, which is known to some academics but unknown to most people, in an accessible book. Hence came “The Islamic Moses.”

Why do you think Moses is mentioned so much more frequently in the Quran than Muhammad?

Muhammad leads Abraham, Moses, Jesus and others in prayer. Persian miniature, 15th century. (Public domain)

Wishing to better understand Islam, a Christian friend once asked US-based Turkish writer, intellectual and journalist Mustafa Akyol to recommend an English translation of the Quran for him to read. A few weeks later, after completing Muhammad Abdel-Haleem’s “The Qur’an: A New Translation,” the friend continued his conversation with Akyol. He had some thoughts and had been grappling with some passages that he found notably opaque or troublesome — yet one thing struck him as the biggest surprise of all.

“I was expecting to read about the life of Muhammad, but instead I read about the life of Moses more than anything else,” the friend wrote.

Moses is mentioned 137 times in the Quran, while Muhammad is mentioned just four times. And who is the second most common character in Islam’s holiest text? Another figure from the Jewish Bible — Moses’s nemesis, Pharaoh.

That certainly is not by chance, as Akyol points out in his new book, “The Islamic Moses: How the Prophet Inspired Jews and Muslims to Flourish Together and Change the World.”

The biblical characters and narrative were, in fact, intentionally central to the new faith Muhammad was cultivating and promoting across Arabia and beyond some 14 centuries ago.

Get The Times of Israel's Daily Editionby email and never miss our top stories

Newsletter email address Get it

By signing up, you agree to the terms

Moses and his story were emulated by Muhammad, and the parallels are not hard to spot. Both men started as unlikely leaders — Moses, slow of speech, and Muhammad illiterate — and yet both ultimately led massively successful migratory, nation-building and military efforts alongside the establishment of new religious-legal systems: Jewish halacha and Islamic sharia.

In the book, Akyol examines further theological parallels, yet also explores historical encounters between the Jewish and Islamic worlds. The author finds these interactions especially important in the current geopolitical climate, in which many forget that for much of history, the Judeo-Islamic tradition was much more peaceful, fruitful and coherent than the Judeo-Christian one.

A partial view of the Nabi Musa complex, where the tomb of Prophet Moses is believed to be located, in the Judean Desert near the West Bank town of Jericho, on January 2, 2021. (HAZEM BADER / AFP)

Some of those encounters — such as the mass migration of exiled Iberian Jews into Muslim lands in the 15th and 16th centuries — are well-known. Others — like Jews celebrating the initial Muslim conquest of Jerusalem, which facilitated some 1,400 years of nearly uninterrupted Jewish settlement in the Holy City after Christians had long barred them from residing there — are less well-known.

Advertisement

Akyol doesn’t overlook some of the darker historical periods in Jewish-Muslim relations, such as the persecution and forced conversions under the Almohad Caliphate, though he treats these as largely the exception rather than the rule, and they are certainly not the book’s focus.

Mustafa Akyol. (Richie Downs for Cato Institute)

A senior fellow at the Cato Institute and a prolific author, Akyol often explores the intersection of Islam and modernity, as well as other cultures and faiths. His previous books include “Islam Without Extremes: A Muslim Case for Liberty”; “Reopening Muslim Minds: A Return to Reason, Freedom, and Tolerance”; and, perhaps most similar to his latest work, “The Islamic Jesus: How the King of the Jews Became a Prophet of the Muslims.”

The Times of Israel asked Akyol about the impetus for examining the Islamic Moses, what most surprised him during the course of his research, and what relevance he sees in the Judeo-Islamic tradition in today’s post-October 7 reality.

The Times of Israel: What triggered you to explore this topic?

Mustafa Akyol: For decades, as a believing Muslim, I studied the Quran and the Islamic tradition with a growingly interfaith perspective. One thing that struck me is the similarities between Islam and Judaism, from their staunch monotheism to dietary laws, to the primacy of law, the halacha and the sharia, respectively. The more I read about these similarities, as well as the historical connections between Jews and Muslims, I became aware of a “Judeo-Islamic tradition,” as the late great Bernard Lewis called it, and I wanted to tell this story, which is known to some academics but unknown to most people, in an accessible book. Hence came “The Islamic Moses.”

Why do you think Moses is mentioned so much more frequently in the Quran than Muhammad?

Advertisement

The dominance of Moses in the Quran is indeed fascinating. His name is mentioned some 137 times, while the name Muhammad is mentioned just four times. I believe there are two reasons for this: First, the Quran does not speak much about Muhammad, because it speaks to him. It tells him about the stories of former prophets, to guide and encourage him for his own mission.

Second, among these former prophets, Moses is the most important one, because he was the key role model for Muhammad. Just like Moses, Muhammad led his believers from persecution to freedom — through an exodus or hijra. Afterwards, both men gave divine laws to their believers, and also set them on conquest — the Conquest of Canaan and the Conquest of Hejaz.

Pointing to such parallels, Patricia Crone, a Western scholar of Islam, defined Moses as the “paradigmatic prophet” for Muhammad. I agree, and I think that also makes Judaism the paradigmatic religion for Islam, which also means that Jews and Muslims have similar challenges in the modern era: How to make humane sense of the belligerent passages in your scripture, or how to live by your religious law without aspiring for oppressive theocracies, and perhaps reforming it to some extent?

What made you decide to discuss both theological parallels and historical encounters between Jews and Muslims rather than just sticking with one or the other? What original examples or insights do you think your book brings to the general public’s attention that previous works haven’t?

I discuss both theological parallels and historical encounters because I believe they are connected. From the beginning, Islam considered Judaism as a legitimate form of monotheism, which allowed Jews to practice their religion under Muslim rule. The “dhimmi” [tolerated, but also subdued] status offered to Jews was quite short of the equal citizenship we enjoy in the modern liberal world, but for its time, it was the best deal that Jews could find. Hence, Muslim conquests were welcomed and even aided by Jewish communities, and there have been waves of Jewish immigration to Muslim lands.

This co-existence also allowed a “Jewish-Muslim symbiosis,” as the late Jewish historian Shelomo D. Goitein called it, which includes mutual learning. Muslims learned from “Israilliyat,” or “Israelite sources,” while Jews learned from Muslim theology, philosophy and even Sufism.

My book brings such themes covered by expert historians and theologians together in one big accessible story. It also highlights very little-known facts, some from the Ottoman tradition that I am familiar with. Readers may be surprised to learn, for example, that the last Ottoman Caliph, who was expelled from Turkey in 1924, had received the warmest farewell from an Ottoman Jew. It is a story related in the memoirs of the secretary of the last caliph, and is unknown to most Turks, as well.

You’re an accomplished writer, scholar and researcher. While working on this book, were there historical encounters between Jews and Muslims that you’d never heard about before? What was the most surprising thing you discovered during the course of your research?

Thank you for your kindness. I certainly learned much more about certain themes that I knew only superficially. It was interesting to learn, for example, that after his conquest of Jerusalem in 638 CE, Caliph Umar had to negotiate with Christians to be able to resettle Jews in the Holy City — and that this was seen by some Jews as the sign of a messianic age, as we observe in “The Secrets of Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai.”

Or, it was interesting to learn how Abraham Maimonides, the son of the Rambam [Rabbi Moses ben Maimon], embraced Sufism and even tried to introduce some Islamic practices into Judaism, believing they were originally Jewish anyway. Or the 19th-century Jewish sympathy and support for the Ottoman Empire across Europe… Jack Miles, who kindly wrote a powerful blurb for my book, says that it “surprises again and yet again.” That was my own experience, too, while writing and discovering certain themes.

What do you think Muhammad’s response to the October 7 attacks and subsequent regional war would have been?

I am generally cautious about guessing “what Muhammad would do,” as people often do that by projecting their own views back to him — or to Jesus, if they are Christian. But, given his recorded commandments about the ethics of war, I can say that he would probably condemn intentional violence against non-combatants. His first caliph Abu Bakr also clearly commanded, “Do not kill women or children or an aged, infirm person.”

Based on those, I have condemned terrorist attacks committed against Israeli civilians — on October 7 or during the so-called Second Intifada. It is no wonder that those who justify these attacks refer to modern concepts, such as “settler colonialism,” which has no counterpart in Islamic law, which only distinguishes between combatants and non-combatants in war.

And, of course, the same principle applies both ways. I also have condemned all indiscriminate violence inflicted on civilians on the Palestinian side. And I have been horrified to see people justifying it — with either modern arguments [such as “they voted for Hamas”], or religious ones [such as “they are Amalek”].

Many have discussed the polarizing effects of mass media, and specifically social media, on modern culture and society. Certainly, social media has led to increased extremism and polarization generally, and specifically over the last year, with regard to the conflict in the Middle East. Yet technology can also connect people with disparate views from different cultures and places.

Realistically speaking, do you see technology somehow helping to bridge cultural gaps and decrease polarization and extremism in any way, or should we simply expect the opposite to continue being the prevalent reality?

Communication technology, I think, simply gives us more effective tools to disseminate our ideas. These could be good or bad ideas, and it is us, not technology itself, which makes the choices. An analogy could be the invention of the printing press centuries ago, which made books much more easily printable and available, but they could be wonderful books on love, mercy and empathy, or evil books like “Mein Kampf.” And to counter terrible things like the latter, we needed not to ban books, but to defeat bad ideas with better ideas. I see the challenges brought by the internet and social media in the same way.

Despite the reverence we find in the Quran for the Jewish people, there are also several verses that look upon Jews as something less than admirable. There are well-known verses describing Jews as “apes and swine” (5:64-65), for example, and other places where despite Jews being referred to as the “People of the Book,” there seems to be some sort of divine authorization to kill them (33:26). Muslim extremists may be inspired by these types of sources to hate Jews and kill them, while Jewish and other skeptics see them as proof that Islam is in its nature an antisemitic and violent religion. Are they wrong? What would you say to both of these groups?

Thanks for asking about this issue, which I do cover in my book in detail. Briefly, I can say there are passages in the Quran that have been used to fuel hatred against Jews, either by taking them out of context or even distorting their meaning.

For example, the “apes and swine” passage that you rightly asked about (5:60), actually does not call Jews as such. It only says some disobedient Jews in some distant past were turned by God miraculously into those creatures, which does not say anything about the Jewish people in general. This is how most classical Muslim exegetes understood it, as I note in my book, but it was turned into an antisemitic trope in the 20th century.

As for the “divine authorization to kill them,” as you put it, that is only a reference to the siege of the Banu Qurayza tribe in Medina in the year 627. It is a disturbingly violent story, indeed, which I revisit in my book. Briefly, that Jewish tribe was targeted not because they were Jews, but because they collaborated with the enemy forces that had besieged Medina. Second, I question the authenticity of later [post-Quranic] reports about this incident, which say hundreds of men were executed.

I can confidently say that there is nothing in the Quran that justifies violence against Jews for their religion or identity. On the other hand, there are polemical passages, but they should be understood within the political context of Medina at the time of Muhammad.

As you mention in your book, when Jerusalem was conquered by the early Muslims, they allowed Jews to live there — something that was forbidden under Christian rule. Jews even celebrated their arrival, and it seems clear that there is space in Islam to accept Jews living in the Land of Israel. What about modern Zionism and Jewish sovereignty? Is that more problematic, or is there also a place for that to be accepted within Islamic thought and law?

Indeed, Muslims never had a problem with Jewish presence in the Holy Land. Muslims, in fact, helped Jews return to Jerusalem twice: after their violent expulsion first by the Romans and then by the Crusaders. True, Jews were still second-class citizens under traditional Islam, but the Ottoman Empire, the seat of the Caliphate, abolished that dhimmi status in the mid-19th century, granting equal citizenship to non-Muslims, including Jews. Hence there were Jewish deputies in the Ottoman parliament.

As for Jewish sovereignty: I look at this from an Ottoman perspective. That diverse empire gradually collapsed, and its people established over two dozen modern nation-states. Some are Christian-majority states such as Serbia, Greece, or Bulgaria. As a Muslim, do I have a problem with them? No, I don’t, as long as they do not harm my co-religionists, or other innocent people, which they did in the darker periods of their history.

With Israel, too, I don’t see any Islamic reason to oppose Jewish sovereignty, as long as it grants freedom, security and equality to Muslims living under its rule. But I am afraid that has not been the case since 1967, with millions of Palestinians in occupied territories given neither citizenship nor a country of their own. That is why I have been an advocate of a two-state solution — or any solution that Israelis and Palestinians can agree on. So that both peoples in the Holy Land, from the river to the sea, can live together side by side, equally safe and free.

.jpg)