On very special occasions, when the conditions perfectly align, the Moon conceals the Sun and blackness sweeps across the sky, according to BBC News.

Although total solar eclipses only last for a few fleeting moments, they can have profound effects on humans, inspiring feelings of awe and wonder. But it's harder to predict how animals will respond when they are plunged into darkness in the daytime.

Animals rely on a 24-hour biological clock, known as their circadian rhythms, to control daily behaviours such as sleeping, foraging and hunting. The way eclipses disrupt these ingrained routines is relatively unexplored, as cosmic events are such rare phenomena – occurring in any given place roughly once every 400 years – and also, because not all animals react the same.

"[Light] is such a huge cue that affects everything from plants to animals. As biologists we can't turn off the Sun but every now and then, nature turns it off for us," says Cecilia Nilsson, a behavioural ecologist at Lund University in Sweden.

More than 100 years ago an entomologist from New England put the Sun's disappearance to the test. William Wheeler circulated adverts in local newspapers, recruiting the public to record changes in animal behaviour during a 1932 solar eclipse. He gathered more than 500 anecdotes, which charted changes in birds, mammals, insects and plants, including owls starting to hoot and bees returning to their hive.

In August 2017, an eclipse which blotted out the Sun's rays for two minutes and 42 seconds, allowed scientists to repeat this experiment. This time, the spectacle had more surprising results. As darkness approached, giraffes galloped nervously and tortoises mated in a South Carolina zoo, and bumblebees stopped buzzing in the states of Oregon, Idaho and Missouri.

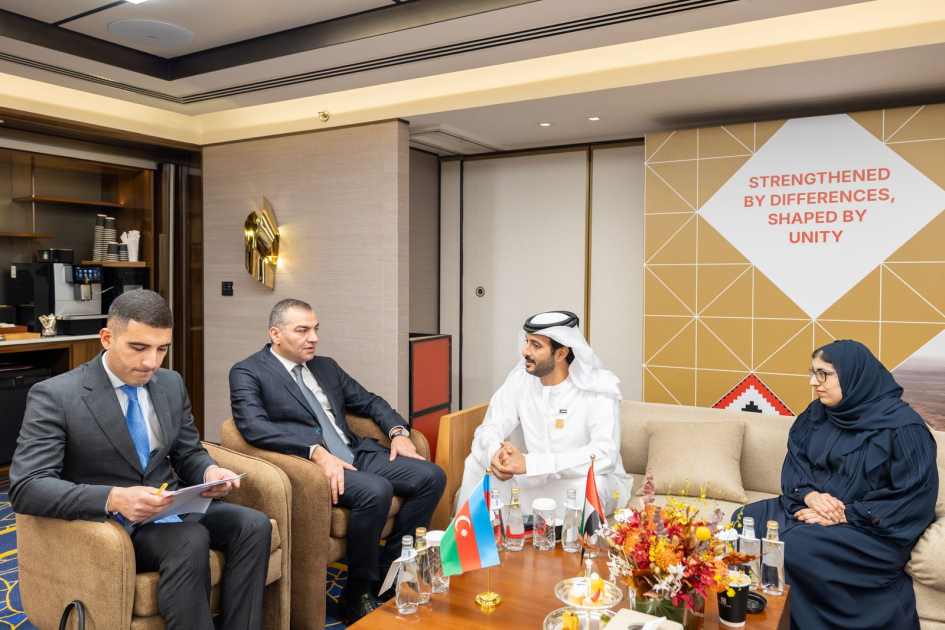

With the next solar eclipse taking place on Monday (8 April), curiosity has been piqued once again. Spanning a narrow strip of land, from Mexico to Maine, scientists will be watching the path of totality closely, and calling on people to note down any mysterious behaviour.

Adam Hartstone-Rose, a scientist who works with the Riverbanks Zoo and Garden in South Carolina, initially thought the zoo's inhabitants would be unfazed by the 2017 eclipse – shrugging it off like clouds passing or a rainstorm, he says.

Despite this, trained researchers and hordes of citizen scientists gathered at the zoo to observe 17 species before and after the eclipse. "It was remarkable because the zoo was bonkers that day. There were thousands of people, everybody was excited," he says.

More than three-quarters of animals that were observed had a discernible reaction to the "amazing" and "life-changing" event, says Hartstone-Rose.

The medley of reactions were categorised into four traits – animals who acted normally, those who performed their evening routines and those displaying anxiety or novel behaviours.

Some animals, such as grizzly bears, were totally nonplussed about experiencing a rare cosmic event. "They were basically sleeping and chilling during the whole experience," says Hartstone-Rose. "Right at totality one of them flopped his head over, almost to emphasise that he couldn't care less," he adds.

Nocturnal birds, on the other hand, seemed very confused. "During the daytime, tawny frogmouths try their best to look like a rotting tree stump," says Hartstone-Rose. The master of disguise, these birds shake their camouflage off at night to forage for food. "That's exactly what they did just at the peak of totality. When the Sun came back out, they went back into tree branch mode," adds Hartstone-Rose

Sadly, some animals showed symptoms of anxiety and distress during the eclipse. Giraffes, which are "usually pretty relaxed animals", says Hartstone-Rose, began running as if startled by a predator or vehicle in the wild. This mirrored giraffes at the Nashville Zoo in Tennessee, which grew nervous and began galloping after totality.

But the strangest behaviour came from the Galapagos giant tortoises. "Normally, tortoises are pretty sedentary and not very expressive animals," says Hartstone-Rose. However, they became more extroverted and active leading up to the eclipse – spontaneously mating with each other at the peak of totality.