Antimicrobial resistance is already killing millions around the globe, but deaths could surge by 68 per cent between 2021 and 2050, Euronews reports citing a major new study.

More than 39 million people worldwide could die from antibiotic-resistant infections over the next 25 years, and another 130 million could die of related causes, according to a landmark new study that comes days before global leaders convene in New York to sign off on a pledge to combat the growing public health threat.

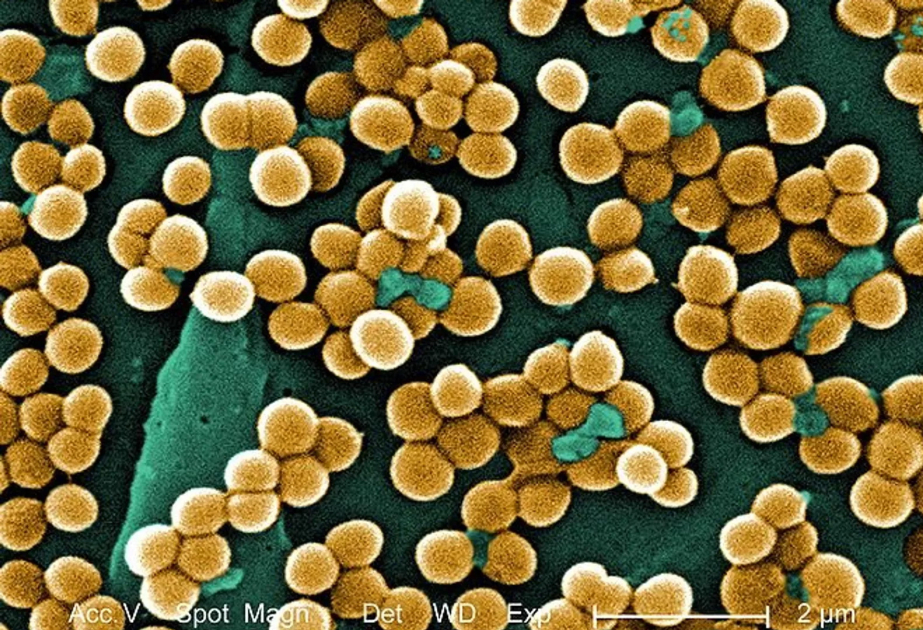

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) – when bacteria or other pathogens evolve to the point where antibiotics are no longer effective against them – happens when people overuse antibiotics in medicine and animal and crop farming.

These so-called superbugs make infections harder to treat as doctors scramble for alternatives, and have directly killed about a million people every year since 1990, according to the new study, published in The Lancet journal.

The hazards of AMR are on the rise. By 2050, there could be 1.91 million deaths directly from AMR and 6.31 million deaths from AMR-related causes, meaning a drug-resistant infection played a role in someone’s death, but resistance itself may or may not have been a factor, according to the new estimates from the Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance (GRAM) Project.

For the new study, researchers used 520 million records to estimate the number of deaths and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) – a quality-of-life measure – that can be directly attributed to or associated with AMR across 22 pathogens, 84 pathogen-drug combinations, and 11 infections. The analysis spanned 204 countries and territories.

They found that from 1990 to 2021, AMR-related deaths fell by roughly 60 per cent among children younger than 5, but surged by more than 80 per cent for adults 70 and older. That’s because vaccination programmes and other infection prevention and control measures protected children, and because many countries’ ageing populations left older people vulnerable.

Older people will continue to bear the brunt of the rising death toll in the coming years, the analysis shows. But they are far from the only ones at risk.

People in South Asia, including India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, as well as other parts of southern and eastern Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean, are also expected to be hard hit.

According to the Lancet study, many of the projected AMR deaths could be curtailed with a few key measures such as better infection control, widespread immunisations, the development of new antibiotics, and minimising their use when it isn’t necessary in medical and farm settings.

With improved antibiotic access and better infection care, for example, 92 million deaths could be avoided between 2025 and 2050. If drugs are developed to target Gram-negative bacteria – which are some of the most antibiotic-resistant – 11.1 million deaths could be averted.

Across the European Union, average microbial use for medical treatment fell by 2.5 per cent between 2019 and 2022, indicating the bloc is making “slow progress” toward its goal of curbing use by 20 per cent by 2030, according to the EU public health agency.