ByJERUSALEM POST STAFF

Palmira Saladié : "The vertebra shows sharp incisions at important anatomical points for the disarticulation of the head".

Archaeologists discovered new evidence of cannibalism among early human ancestors at the Gran Dolina cave site in northern Spain. The remains, belonging to Homo antecessor, an extinct species of early humans that lived around 770,000 years ago and known only from the Atapuerca site, reveal that even children were not exempt from this practice. According to Live Science, researchers analyzed a child's neck bone found in the cave system, which belonged to a toddler aged between 2 and 5 years.

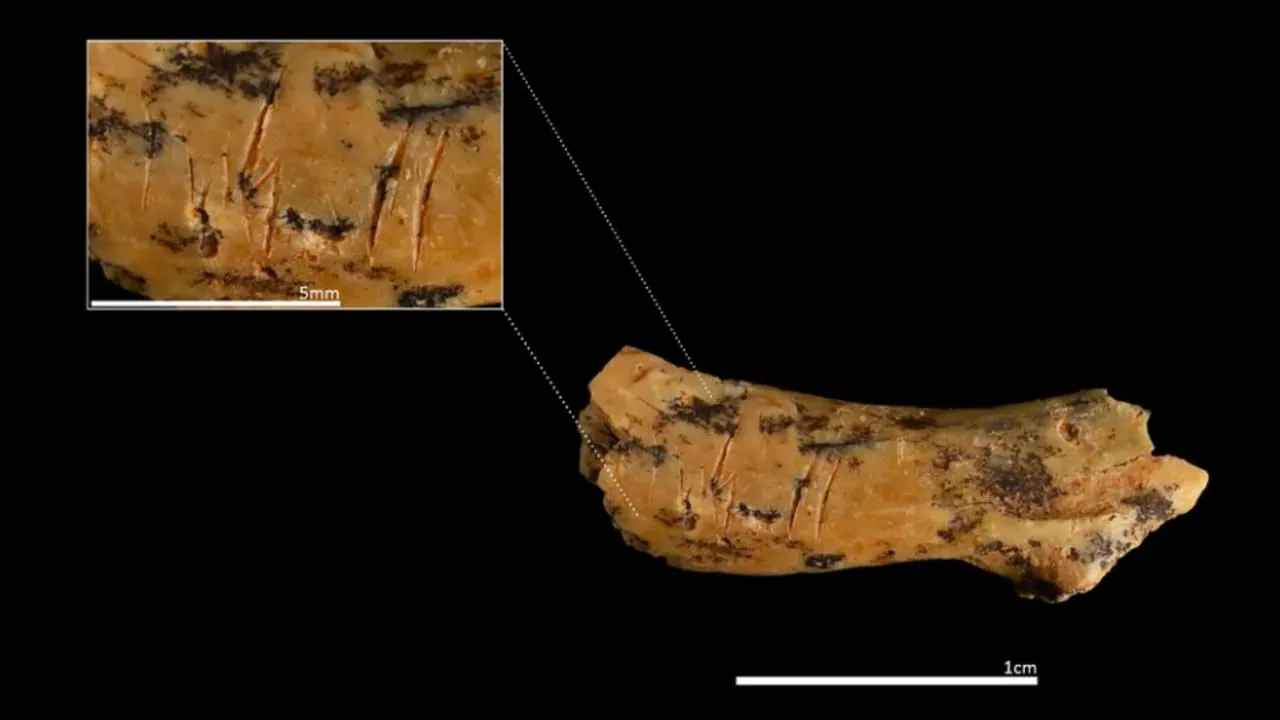

The bone shows cut marks—signs of decapitation and defleshing—indicating that the child was treated like any other prey. "This case is particularly impressive, not only because of the age of the child, but also because of the precision of the cuts. The vertebra shows sharp incisions at important anatomical points for the disarticulation of the head. It is direct evidence that the child was processed like any other prey," said Dr. Palmira Saladié, co-director of the Gran Dolina excavation, according to Live Science.

Over three decades of excavation, the Gran Dolina Cave has revealed more than two dozen examples of human cannibalism. Researchers from the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES) reported that about 30% of the human bones found at the site show signs of cannibalism, including slicing, smashing, and bite marks. "The preservation of the fossil surfaces is extraordinary," Saladié told Live Science in an email. "The cut marks on the bones do not appear in isolation. Human bite marks have been identified on the bones—this is the most reliable evidence that the bodies found at the site were indeed consumed."

Experts believe that cannibalism at Gran Dolina wasn't just a survival strategy; it may have also helped these hominins assert control over territory or reduce rival groups. "What we are documenting now is the continuity of that [cannibalism] behavior. The treatment of the dead was not exceptional, but repeated," Saladié said. The research team indicates that infant cannibalism was associated with systematic practices of meat exploitation by Homo antecessor, making these bones the earliest definitive example of human cannibalism to date.

Homo antecessor, the earliest human relative found in Europe, lived between 1.2 million and 800,000 years ago and were, on average, thicker and shorter than modern humans. Since their discovery in the 1990s, experts debated whether Homo antecessor was the ancestor of Neanderthals and modern humans or an offshoot of the human lineage, and its exact position in the human family tree is still unclear. The species baffled scientists with a strange mix of features: some modern, some not.

Identification of cannibalism was possible because the marks on the bones are characteristic signs of meat exploitation identical to those observed in the remains of animals consumed by these same humans. Archaeologists observed traces of cuts on a toddler's neck bone, indicating a deeply unsettling fate.

Evidence of cannibalism among early human relatives dates back even further. In Kenya, cut marks on bones dating back 1.45 million years suggest possible cannibalism, though it's less clear whether those marks are from cannibalism or something else. The bones found at Gran Dolina, however, are the earliest definitive evidence of human cannibalism anywhere. "This means cannibalism at Gran Dolina wasn't a one-time tragedy," experts say. "In the Gran Dolina cave, prey was often another human."

According to the researchers, everything indicates that the TD6 level still hides numerous human remains in the layers yet to be excavated, which could shed light on the human relative Homo antecessor. "Every year we uncover new evidence that forces us to rethink how they lived, how they died, and how the dead were treated nearly a million years ago," Saladié said.

The research has been conducted by the Institut Català de Paleoecologia Humana i Evolució Social of the Universitat Rovira i Virgili. This superposition of human and carnivore occupation helps reconstruct the alternate use of the cave and provides clues about competition between species in a hostile environment.